Apocalypse Now review: Can a film be anti-war?

Some say it's possible while director Francis Ford Coppola disagrees with the sentiment regarding his complex interpretation of the Vietnam War

A film I watched recently for the first time is Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979). It explores what happens to those who view others as the ‘enemy’ and are placed in conditions that affect their already tormented minds, leading to moral wretchedness in the face of war. A madness that destroys everything in its path.

On the subject of colonialism and its violence, the film reminded me of Frantz Fanon's book "The Wretched of the Earth." Published in 1961, it was written at the height of the Algerian war for independence against the French. It offers a psychoanalysis of the effects of colonialism on individuals and examines its broader impact on nations by analysing the roles of race, class, and national culture in the struggle for freedom against oppression.

Although Apocalypse Now and The Wretched of the Earth are different forms of media, they both have shared themes in how they grapple with violence, colonialism and psychological trauma. Coppola's film presents political cynicism and the descent into madness unleashed in an unrelenting hellscape. In Fanon's book, he analyses how colonisation causes mental disorders in making the colonised feel inferior while the colonisers act superior.

Is it an anti-war film? Coppola doesn’t think so. “It shouldn’t have sequences of violence that inspire a lust for violence. Apocalypse Now has stirring scenes of helicopters attacking innocent people. That’s not anti-war.”

There are scenes in Apocalypse Now where such beliefs are displayed. In the extended Redux version, a French family clings to the remnants of France’s colonial legacy in the region. They lament about the good old days and their superiority over the natives during dinner with a group of American soldiers at their plantation in Vietnam. This scene showed their delusions and perceived domination of Vietnamese people, reinforcing the mentality that colonists have. Their presence is like a haunting reminder of imperialism’s ghost.

The cowboy hat-wearing, surfing-obsessed Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore– played by Robert Duvall (The Godfather trilogy), is another hypocritical and immoral character with theatrical ideals of war. Alongside his soldiers, they brutally attack innocent Vietnamese civilians whom they call ‘savages’ for wanting to defend themselves against the onslaught of violence. Richard Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries plays in this scene as American soldiers rain bombs from their helicopters, displaying satisfaction and bloodlust like something out of a horror film, which Apocalypse Now practically is.

It’s adapted from the 1899 novella Heart of Darkness by Polish-British author Joseph Conrad. In the book, sailor Charles Marlow narrates the story of his task as a steamer captain for a Belgian company to find the man known as Kurtz, who lost his mind in an African jungle. Though not as obvious where the book is set, Heart of Darkness is inspired by the real-life journey Conrad took up the Congo River in 1890 during King Leopold II of Belgium’s reign of terror. It’s a story into the depths of depravity of the human soul and the darkness of colonialism. Like Coppola’s film, the unsettling journey is filled with bizarre and menacing moments that feel like a suffocating cloak you can’t take off.

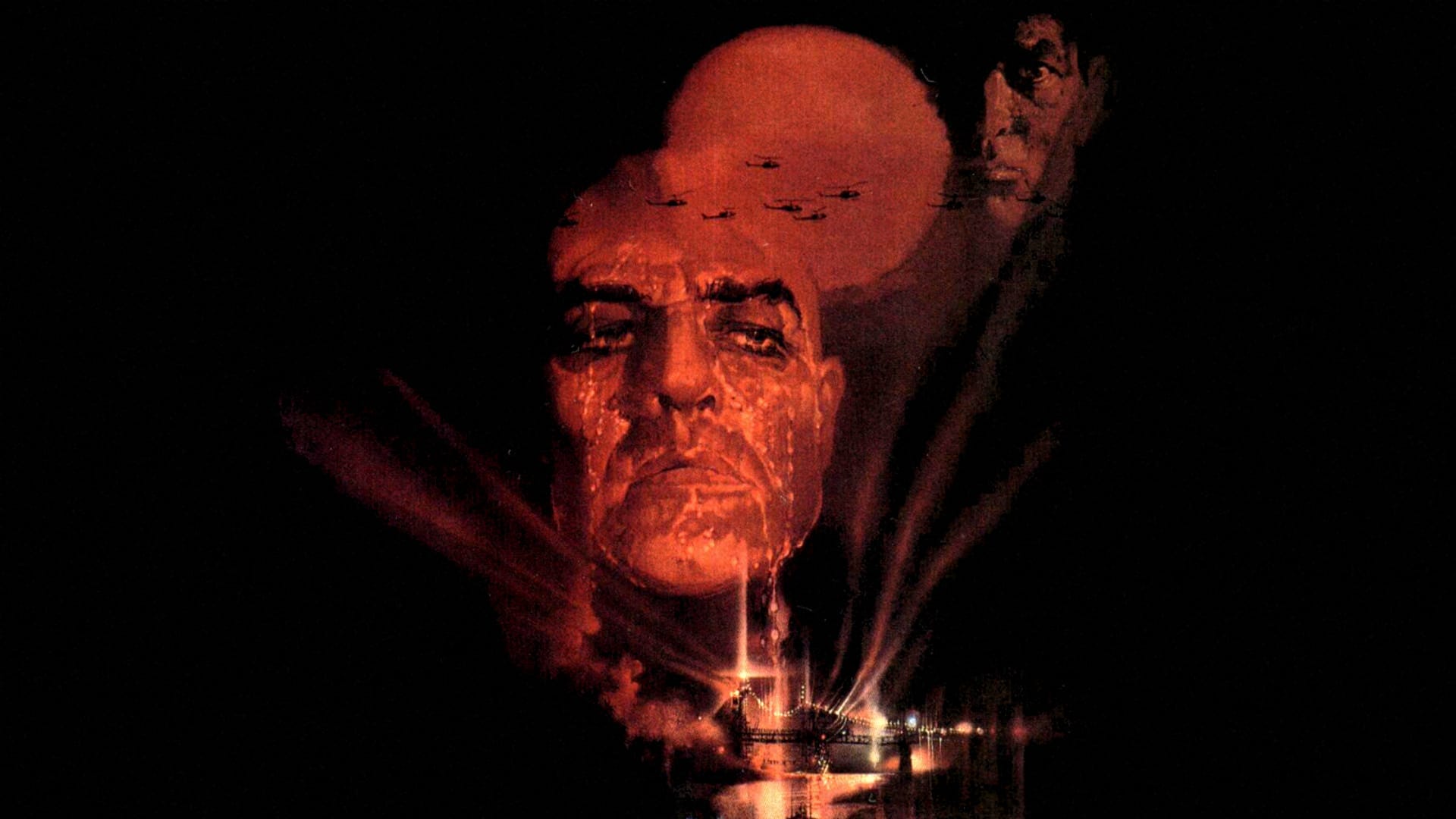

With a screenplay by John Milius and co-written by Coppola, Apocalypse Now centres Conrad’s book but changes its setting to the war in Vietnam and Cambodia. It stars Martin Sheen as the tormented Captain Benjamin L. Willard who suffers PTSD from his previous tour in Vietnam as his superiors assign him on a secret mission to find and kill the darkly enigmatic Colonel Walter E. Kurtz (masterfully played by Marlon Brando), who went rogue in the humid and claustrophobic jungles of Vietnam. By the time Willard finds him, Kurtz is worshipped similarly to a pagan god. He’s a cult-like, colonial figure taking advantage of the openness of the Vietnamese people. Kurtz disguises his true intentions as a ‘saviour’– even convincing himself, standing up for the people, meanwhile, he runs rampant in his small kingdom committing atrocities he wouldn’t get away with back in America.

At first, I didn’t know what to make of the over 3 hours director’s cut of Apocalypse Now, except that it went on longer than it needed to in certain scenes (I see why some prefer the theatrical release version). However, I thought about it differently later on. I couldn’t shake off how deeply unnerving the film is. Not only on the portrayal of western imperialism atrocities worldwide and its ironies (do as I say, don't do as I do or rebel), but also on the human cost of the Vietnam War. From ordinary citizens with grandiose dreams of conquest and heroism being drafted to fight the wars their governments create for superpower status– masked as democracy, to primarily the victims of colonialism.

Several scenes in the film appalled me. Mainly when a Vietnamese family is viewed as a ‘threat’ and massacred when the only thing they were hiding is a puppy. The casual problematic dialogue between the characters also leaves little to be desired. Though certainly fitting for the period. There’s a famous line by Kilgore saying “I Love the Smell of Napalm in the Morning” that encapsulates the absurdity and senseless violence in the film. Willard is told to act more like Kilgore to get the job done. In reality, it’s a mindset soldiers are encouraged to adopt as instruments of war.

There’s a stifling feeling of impending doom throughout Apocalypse Now. It’s not a straightforward watch, but has a nuanced and complex philosophical commentary on the Vietnam War and how, when given the opportunity, everyone is capable of violence especially if the tendency is already there and exploited by those in power. On the other hand, Conrad’s book has been critiqued for having an ambiguous nature of the colonial system and its impact on individuals and the country.

Apocalypse Now delivers a beautiful and surreal cinematography by Vittorio Storaro. It’s like a moving painting while trapped in a heady, hallucinatory dream that’s both eerie and has an air thick with tension. A bleak atmosphere that at times is a sensory overload with all the things happening in various scenes– escalating further with the encompassing sounds: flying helicopters, persistent gunfire, bombs exploding, people shouting or screaming. This disturbing film will stay with you after watching it and also serve as a reminder that unfortunately, not much has changed in society. We’re constantly bombarded by news of war in other parts of the world. The recent skirmish between India and Pakistan regarding Kashmir comes to mind. They both have nuclear weapons…

Several war films since Apocalypse Now have been released (Hollywood is a fan of war propaganda films like American Sniper, where the audience is directed to sympathise with the main perpetrators), and it doesn’t look to let up anytime soon. A24 recently released Warfare (2025), which gained a mixed press reaction, with many people frustrated by ‘another war film’ regarding Western forces– primarily Americans, that claim to solve foreign ‘conflicts’ like some supreme judge and jury and keeper of democracy.

Ultimately, there are no winners. Innocents wanting to live their ordinary lives always get caught in the crossfire. Only the military-industrial complex and those holding the reins of power benefit from causing chaos and strife domestically and abroad.

Some might consider Alex Garland’s Warfare an anti-war film like Apocalypse Now, as both focus on the violent realities of combat and the moral breakdown of soldiers. However, it’s not possible to disconnect them from their environment, no matter how it’s been addressed. People still die, lose their homes and are forced to search for safer shores, often away from their homelands.

Coppola said it as much. “I always thought the perfect anti-war film would be a story in Iraq about a family who were going to have their daughter be married, and different relatives were going to come to the wedding. The people manage to come, maybe there’d be some dangers, but no one would get blown up, nobody would get hurt. They would dance at the wedding. That would be an anti-war film. An anti-war film cannot glorify war, and Apocalypse Now arguably does. Certain sequences have been used to rev up people to be warlike.”

It’s quite apt that creating Apocalypse Now would prove to be a nightmare and the stuff of a Hollywood legend. Shooting it in the Philippines (almost took 240 days) presented what can be described as a streak of bad luck. From tempestuous weather elements, to Martin Sheen having a breakdown and near-fatal heart attack (Coppola had a seizure blaming himself for it), Marlon Brando being unprepared for the role, high drink and drug usage, an overrunning of egos, rumours of dead bodies on set and animal abuse, going over the filming schedule and budget– Coppola losing millions of his own money financing it and “declaring on three separate occasions that he intended to commit suicide” if the film fails, and more pushed everyone to their limits. The definition of suffering for art. Coppola and his team gave it their all in the making of this war epic action film.

Eleanor Coppola filmed the behind-the-scenes for the award-winning documentary Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker's Apocalypse. I also watched this and was mindblown by the lengths it took to make Apocalypse Now.